Because you’re mixing people, stakes, and contexts into one bad argument.

People argue a lot about “vibe coding” because they mix very different profiles into one bucket. If you do not separate them, everyone talks past each other.

Here is a simpler way to look at it.

The four profiles

- Vibe coders without tech knowledge

Non‑technical people who use AI tools to get things done. - Vibe‑coder developers

Developers who know how code works and use AI to move faster on low‑stakes work. - Developers who don’t understand vibe coding

Production‑oriented developers who mostly reject it. - Developers who do understand vibe coding

Developers who can switch between strict production mode and fast‑and‑loose vibe coding.

Once you see these four, a lot of the drama makes sense.

1. Vibe coders without tech knowledge

These people:

- Do not really know how code works.

- Use Cursor, Warp, Claude, ChatGPT and similar tools as a problem‑solving layer, not as a coding layer.

- Want a script, snippet, or automation that “just works” and can be thrown away.

For them, vibe coding is a way to unlock capabilities they did not have before. It is closer to a super‑powered spreadsheet than to software craftsmanship.

It becomes a problem only when:

- They mistake this for being a software engineer, or

- Others expect production‑grade engineering from these experiments.

2. Vibe‑coder developers

These are actual developers who:

- Know how to design and ship serious systems.

- Still choose to vibe code whenever the stakes are low.

They accept two uncomfortable truths:

- Most code we write is throwaway.

For every line that reaches production, many more are written, tested, and deleted: one‑off scripts, browser‑console hacks, internal tools that live a week. - There is a lot of code worth having that is not worth writing or reading.

You want outcomes: benchmarks, glue code, scaffolding, small tools. You do not need to lovingly craft every line.

So they:

- Describe what they want.

- Let AI generate boilerplate, UI, and plumbing.

- Review only the critical parts.

The reason you're not looking at the code is not that you cannot, but that it is not worth the time. The code itself is disposable; the result is what matters.

This is the vibe‑coder developer mindset.

3. Developers who don’t understand vibe coding

These developers usually:

- Code only in a professional context.

- See code as a long‑term production artifact.

- Optimize for correctness, maintainability, and risk.

From that point of view, their reaction is logical:

- In production, you should review everything.

- You must understand the systems you are responsible for.

Where it goes wrong is when they apply production standards to personal experiments and low‑stakes hacks, then conclude that all vibe coding is bad.

They miss that there is a huge space of:

“I just want this to work today and I will never touch it again.”

So they look at vibe coders—especially non‑technical ones—and see only chaos.

4. Developers who do understand vibe coding

These developers have the same depth as the previous group but can switch modes.

They know:

- At work and in production, everything gets reviewed.

- In side projects, internal tools, and experiments, you do not need the same level of control.

They:

- Use AI to scaffold, explore, and iterate quickly.

- Keep critical logic small, simple, and readable.

- Treat the rest as replaceable black boxes.

They can understand everyone:

- Why non‑technical vibe coders love the power boost.

- Why strict production engineers feel uncomfortable.

- How to trade off speed, risk, and maintainability.

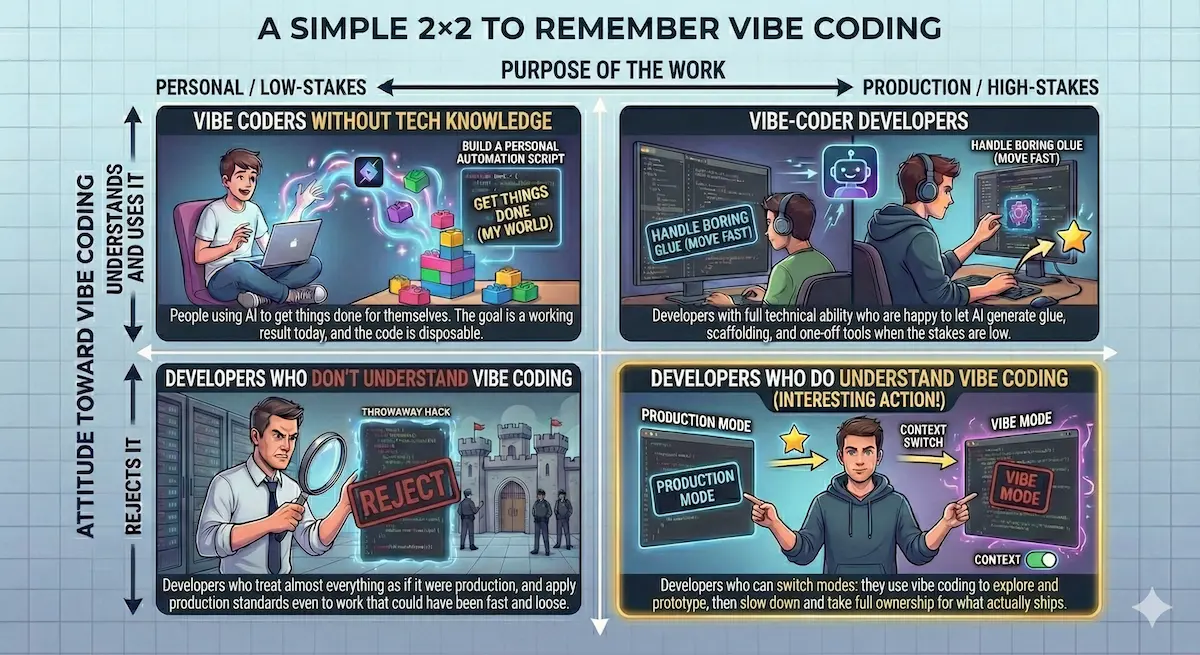

A simple 2×2 to remember

Think of vibe coding on two axes:

- Axis 1: Context → personal / low‑stakes ↔ production / high‑stakes

- Axis 2: Attitude toward vibe coding → understands and uses it ↔ rejects it

Most of the interesting action is in quadrant 4: developers who operate in production but still understand why low‑stakes vibe coding (quadrants 1 and 2) is legitimate. Generally speaking, if you are a developer rejecting vibe coding, it is probably because developing is only a job for you, you don't do experiments outside of work and side projects.

Conclusion: The only question that really matters: context

In the end, it is not about whether vibe coding is good or bad. It is about where you use it.

Ask:

- What is the risk?

- Who is responsible for this long‑term?

- Is this code meant to live, or is it allowed to die tomorrow?

At work, on client or production projects:

- Review everything.

- Own what you ship.

In your personal tools, scripts, and experiments:

- It is fine not to look at every generated line.

- It is fine to throw things away.

There is room for all four profiles—as long as we are honest about the context and stop judging vibe coding with production‑only standards.

Cheers 🍻

Bonus section

An example of tool disagreement: Warp, learning, and the "go deep vs go wide" question

A friend once told me:

"I find that tools like Warp help you move fast but not learn how it works and really improve technically. Go wide or go deep, and I prefer to go deep."

That is a valid position—if your goal is to learn.

My view:

- I do not use Warp or AI on topics where I want deep understanding.

- I use them where I just want to get something done.

Using Warp or AI there is like reading a summary of the course instead of attending the full lecture. If the goal is mastery, the summary is not enough. If the goal is just to pass a small test tomorrow or unblock yourself today, the summary can be perfect.

Some people only have two modes:

- Learn deeply.

- Ship to production.

They do not have a “mess around and see what happens” mode. They do not tinker for fun. That is fine—but it also means they have no personal use case for casual vibe coding.

That does not make these tools useless. It just means they live in a part of the space this person does not visit.

Let's explores other related problems using AI: for YouTube summaries and blog post writing.

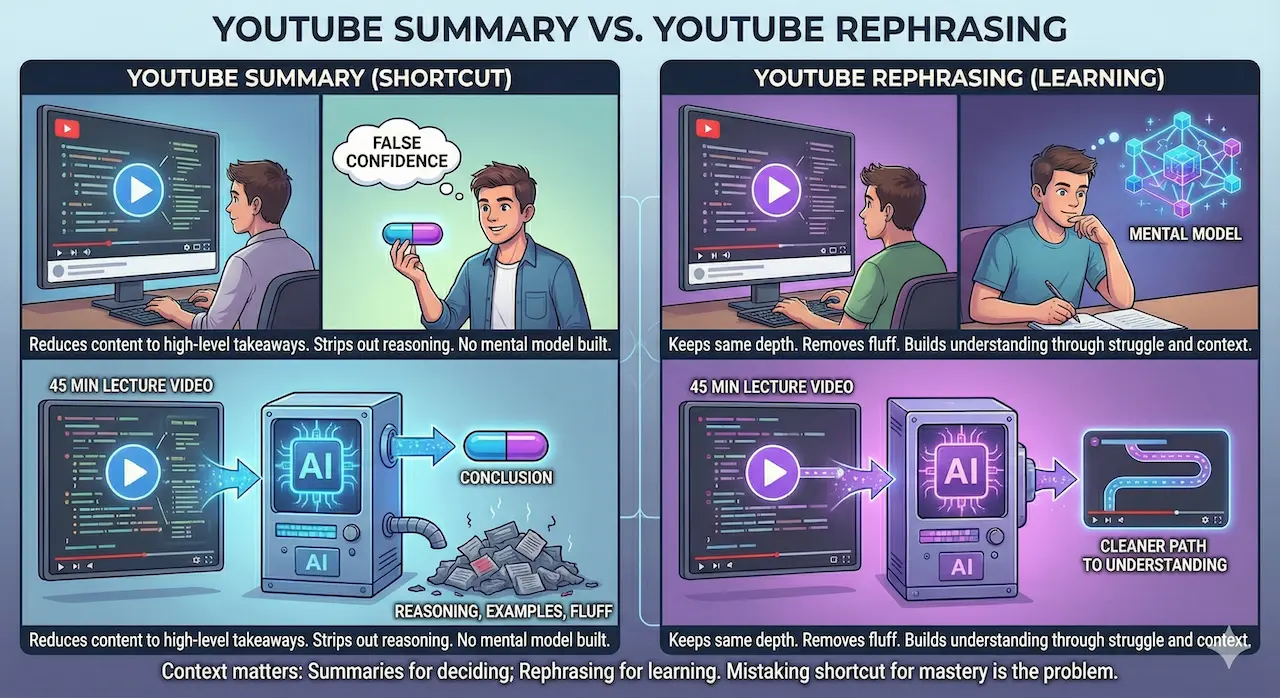

YouTube summaries and the illusion of learning

AI can summarize a 45-minute lecture in two minutes. You get the key points fast.

But if your goal is to actually learn—not just sound informed—the summary is almost useless.

Why? Because most people confuse summarizing with rephrasing.

Summaries vs. rephrasing

Rephrasing:

- Keeps the same depth.

- Removes fluff and awkward phrasing.

- Gives you a cleaner path to understanding.

Summarizing:

- Reduces content to high-level takeaways.

- Strips out reasoning and examples.

- Useful for executives, not learners.

Think about school:

- Would you ask the teacher for a one-sentence recap of the entire lesson?

- Or would you ask them to explain it more clearly, without the filler?

The second one is rephrasing. And that is legitimate.

The problem with summaries for learning:

- Learning requires struggle, repetition, and context.

- Summaries give you conclusions without the reasoning that makes them stick.

- You end up with false confidence.

You got the output, but you did not build the mental model.

So:

- Use summaries to decide if something is worth your time.

- Use rephrasing to learn the content more efficiently.

- If you want deep understanding, do the work—watch, take notes, explain it, apply it.

The problem is mistaking a shortcut for mastery.

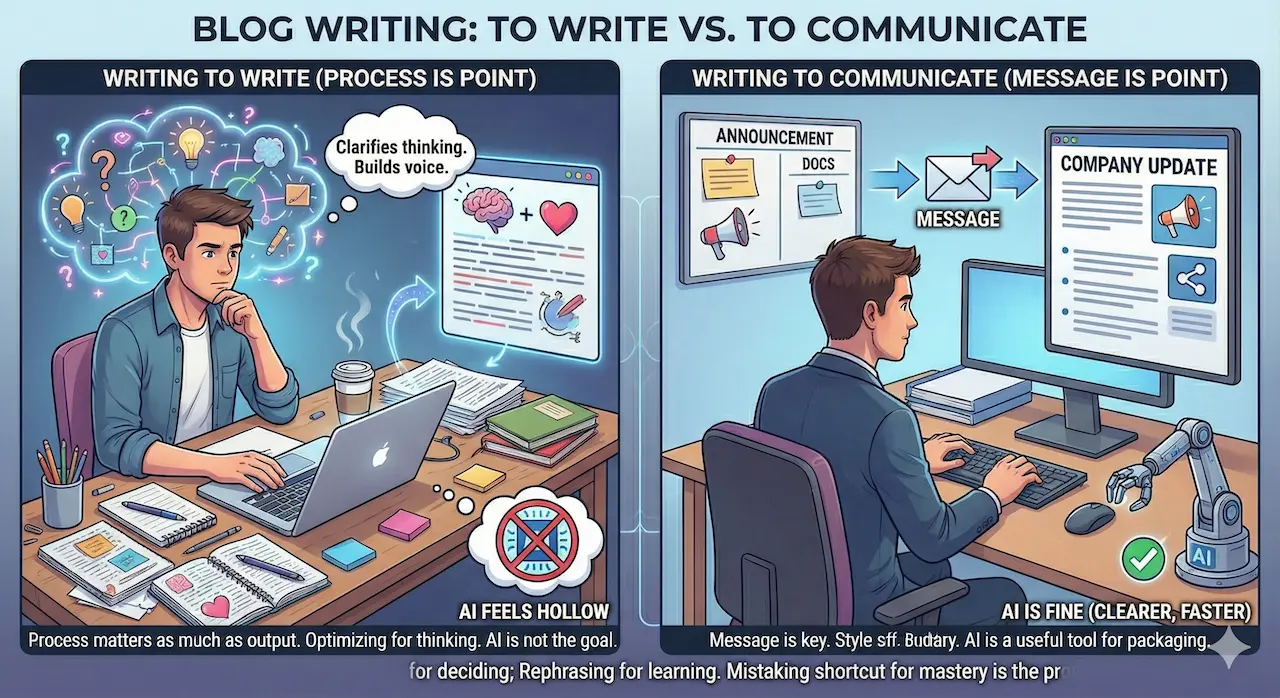

Writing to write vs. writing to communicate

There are two very different reasons people write blog posts, and confusing them leads to bad takes about AI-generated content.

1. Writing to write

- The act of writing is the point.

- It clarifies your thinking.

- It builds your voice.

- The process matters as much as the output.

For these people, using AI to write feels hollow—because they are not optimizing for the artifact. They are optimizing for the thinking that happens while writing.

2. Writing to communicate

- You have a message.

- You need it documented, shared, or published.

- Style and personality are secondary—or irrelevant.

Examples:

- Internal company updates

- Technical documentation

- Policy explanations

- Announcements

For these, AI-generated text is fine. It can even be better—clearer, faster, more consistent.

The blog post might feel "soulless," but that is not a bug. The goal was never to express a unique voice. The goal was to get information across.

It is because I write to communicate that I developed this technique in my Notion AI post which allows anyone to easily create a blog post for this purpose.

The mistake

People who write to write look at AI-generated posts and feel something is missing.

They are right—but only for their use case.

They apply their standard ("does this post reflect deep thought?") to content that was never trying to pass that test.

It is like criticizing a technical manual for not being poetic.

Why this matters

If you conflate these two modes, you end up with two bad positions:

- "AI writing is always fake and bad" → Ignores legitimate communication needs.

- "AI writing is just as good as human writing" → Ignores the value of thinking through writing.

The correct view:

- If writing is the work → do not delegate it.

- If writing is packaging the work → AI can help.

Just like vibe coding, the question is not "is this good or bad?" but "what is the context and goal?"